Dragons appear all throughout Kyoto’s ancient Gion Matsuri. Why are there so many dragons, appearing on so many different levels of the festival? What purpose do they serve? Are they symbols, or specific dragons known in culture and history? To find out, watch the YouTube video recording or read the blogified transcript below.

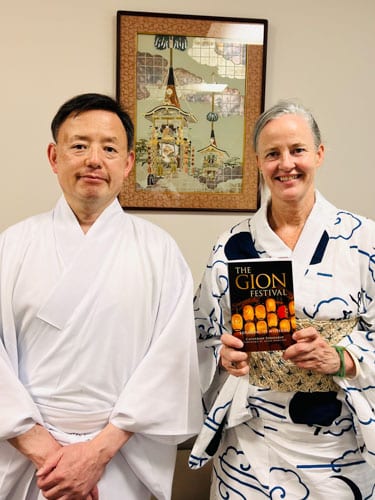

This was a Dec 2022 online presentation hosted by Japan Society Northwest and the JET Alumnae Association, both of the UK. Special thanks to Nomura Guji of Yasaka Shrine, Masashi Nakamura of Japan Code, and Jann Williams of Elemental Japan for inspiring this exploration.

Why Dragons in the Gion Matsuri?

When you think about the Gion Matsuri, these floats (at left) are probably what you think about. They are probably the most famous feature of the Gion Matsuri, the yamaboko floats, and this is the procession on July 17th. It’s quite a spectacular feature of the festival.

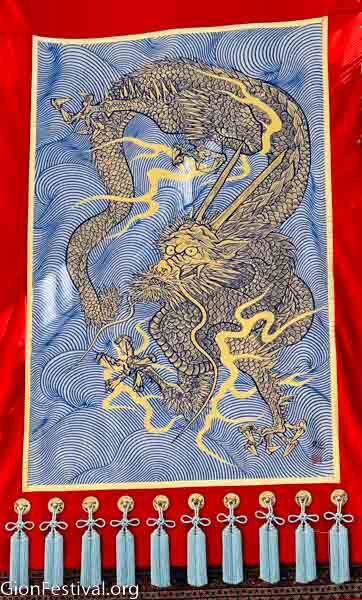

But if you spend a lot of time—or anytime at all—at the Gion Matsuri, you notice that there are a lot of dragons all around the Gion Matsuri. This (see images below, from left) is a textile that adorns a float. Here’s a blue dragon; there’s a lot of dragon metal work, for example; and another blue dragon textile that adorns the Ennogyoja Yama float.

Embroidered dragon detail, Yamabushi Yama.

Blue dragon textile, Ennogyoja Yama.

Embroidered blue dragon, Tsuki Boko.

Metalwork dragon adorning a lacquered rail, Niwatori Boko.

Yasaka Shrine & The God of Storms

So we need to back up a little bit. This (left) is the front gate for Yasaka Jinja, Yasaka Shrine in Kyoto. It’s a famous landmark at the end of Shijo Street, and it’s considered maybe the supreme Shinto shrine in Japan.

Shinto is, most of you probably know as the indigenous religion or spiritual practice in Japan. It’s a nature-based animistic practice, which is basically a form of shamanism.

Yasaka Shrine was founded in the year 656, so it predates Kyoto as the capital (Kyoto became the capital in 794).

Now, the main deities at Yasaka shrine are important in this story. The central deity is Susano-no-Mikoto, that’s the younger brother of Amaterasu, the sun goddess. He’s—significantly—the god of storms.

So, here (right) is a picture of a storm happening during the Gion Matsuri. The festival takes place every summer during the rainy season, the annual rainy season from June to July. And so sometimes it takes place in a downpour like this, even in typhoons.

And below is nearby Shirakawa (“White Stream”) in the Gion neighborhood: Kyoto is a city of water. There are rivers and streams throughout the city.

So, whether or not there are storms is really a significant event for the people of Kyoto and most of Japan.

The First Dragon: Yamata no Orochi

Above we see a woodblock print of Susano-no-Mikoto. There in the middle is the god of storms. He is rescuing his partner, Kushi Inada Hime, that means “Comb Rice-Grain Princess.” She’s on the right there. She was kidnapped by this eight headed dragon on the left, Yamata-no-Orochi. She was kidnapped and held prisoner and Susano-no-Mikoto, the god of storms, went and rescued her. And then they became partners. And so he had to defeat this dragon.

We could say this was the first dragon at the heart of the Gion Festival. Because this story about Yamata-no-Orochi and Susano-no-Mikoto proving himself, and then getting together with Kushi Inada Hime is very central to this story.

The Goddess or Soul of Rice

Kushi Inada Hime is considered the soul of rice. I asked the head priest of Yasaka Shrine if she was the goddess of rice, and he said, “She’s the soul of rice.” I was very impressed by that.

So the deities now at the Yasaka shrine, then, are: Susano-no-Mikoto, the god of storms, the soul of rice, and their children, considered three deities.

Life and Death: Yasaka Shrine’s Ox-Headed Deity

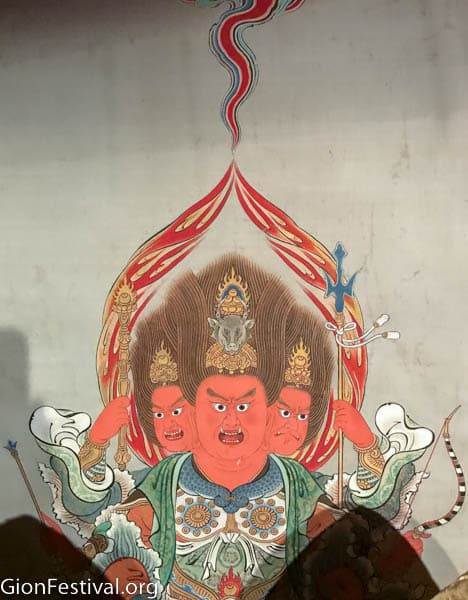

Now, Susano-no-Mikoto is conflated or put together with another deity called Gozu Tenno. That means “ox-headed deity.” And that’s what this scroll (above left) says: it says “Gion Gozu Tenno.” We see scrolls like this all around the Gion Festival. There are very few visual depictions of the ox-headed deity, mostly just the scrolls.

But the next imate (upper right) is a rare one; you can see on top of the front red head is an ox head. This is from the Hashi Benkei Yama collection.

The ox-headed deity is a protector deity, and he’s sometimes called the Lord of Death. But as a protector deity, he guards this threshold between this world and the next world, between life and death.

And that’s really significant because, again, the festival has a lot to do with life and death, as we’ll talk about here in a moment.

Gion Festival Mikoshis’ Purpose

Below are the three mikoshi, or portable shrines, at Yasaka Shrine. And these are carried through the streets of central Kyoto during the Gion Matsuri. There is one for each of the deities: one for Susano-no-Mikoto, the god of storms; one for his partner, Kushi Inada Hime, the soul of rice; and one for their children.

While they’re carried through the streets during the Gion Festival, they’re purifying central Kyoto. They’re bringing their protective and life-nourishing energies to the Kyoto communities and streets.

Then, they rest in central Kyoto for a week. And then the Gion Festival happens. There’s a before part, and an after part.

And this is the central event that the whole Gion Festival revolves around: these mikoshi coming into town to purify the streets and then returning back to Yasaka Shrine.

Kyoto and Feng Shui Energy

Let’s back up a little bit and consider the founding of Kyoto. At right is a model at the Kyoto City Bunka Hakubutsukan, the Bunpaku, the Kyoto cultural museum. This is a map of the ancient capital, Heian Kyo.

When Kyoto was first founded, it was modeled on the Chinese capital city of Xi’an, very much according to feng shui (in English, “geomancy”). You can see all the streets run north-south, and east-west. The directions are very important, as is the flow of energy in those directions.

Practically speaking, one of the wonderful things about this is you can never get lost in Kyoto!

The Water-Ruling Blue Dragon of the East

Why does this matter for the Gion Festival? Well, Yasaka Shrine is in the east of Kyoto, the very eastern part of Kyoto. And in feng shui, each direction has an animal. The blue dragon rules the East, and the blue dragon is also related to the element of water.

So again, we’re tying back to the storms, and this notion of water and the life-giving quality of water. It makes rice and therefore survival possible for the Japanese people.

Yasaka Shrine, Home of The Blue Dragon of the East

At left we see the main hall of Yasaka Shrine. Remarkably, it’s believed the blue dragon lives beneath the main hall. There’s a passageway under this main hall, down deep, deep into the ground, to a kind of cave-like place with a pond. It’s believed that the blue dragon lives in this pond.

In the 1990s I heard that sometime—maybe in the early 1970s or so—they put concrete over the pond, because they thought it was dangerous. Last summer my friend kindly arranged for me to offer my book on the Gion Matsuri to Yasaka Shrine, via its new Head Priest (lower left). I asked him, “Is it really true that there’s concrete over that pond?” And he said, “Yes, there is, and I would like to remove it.”

I was so excited to hear that. Because when you think of the flow of energy, you don’t want your dragon suppressed by a concrete lid, right? The energy is not going to flow properly.

Sacred Water Purifying Kyoto Streets

The Head Priest also talked about the water used to help the floats turn corners in the Gion Festival. We can see at right how water is thrown on bamboo underneath their wheels as lubrication, to help them turn. The head priest described how water was going to be a mixture of water taken from Yasaka Shrine, and from another pond nearby named Shinsen-en.

He got very excited about this, and started talking about Shinsen-en, dragons at Shinsen-en, and Kukai, who you might know as Kobo Daishi, the great Japanese saint of Shingon Buddhism. He talked animatedly about Kukai and dragons at Shinsen-en. I couldn’t quite follow the conversation, but he was so animated about it that I was inspired to follow up.

Shinsen-en Lake & Buddhist Saint Kukai

So below is Shinsen-en Lake. It’s located on Oike Street, and “Oike” means “honorable lake.” This is the lake that Oike refers to. So this lake actually dates back to the founding of Kyoto. It used to be about ten times as big, but it’s the lake from that original Imperial Palace (image with arrow) way back in the seventh century, eighth century.

This lake is still there now. It used to be a pleasure pond from the Imperial Palace. But let’s get back to talking about Kukai.

Drought, Dragons, & Rainmaking Competitions

In the year 824,* there was a terrible drought, causing tremendous suffering. Looking for a solution, the emperor ordered Kukai and another very powerful monk named Jubin to bring rain. They were very high-level, practicing Buddhist monks, and they set to it, trying to bring rain. It turned into a kind of rainmaking competition: who could get rain first, Kukai or Jubin?

Kukai tried and tried, but he couldn’t bring rain. What was he doing to try to cause rainfall? Interestingly enough, he was calling dragons. This was the first time Kukai undertook what came to be known as “The Rain Prayer Sutra Ritual.” It became a tradition that carried on over the next 400 years. He called dragons to bring rain, because the blue dragon rules water, and dragons, in general, are associated with the element of water.

* 2024 will mark the 1200-year anniversary of this ritual.

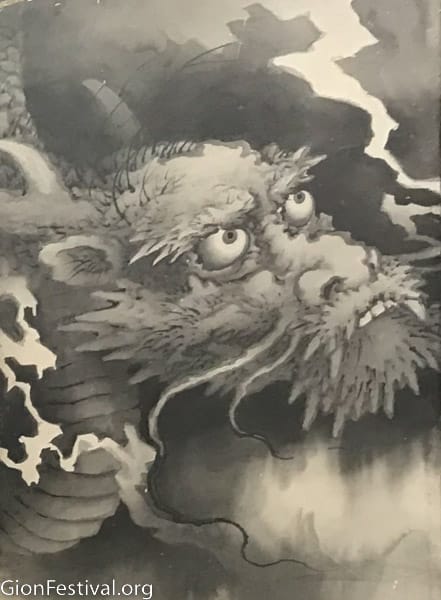

Dragons, Lightning & Storm Clouds in Art

We can see this connection between dragons and rain in artwork. At left is a beautiful dragon folding screen—or byobu—in the Gion Festival. During the Gion Matsuri’s Byobu Matsuri, some local residents and businesses put their personal treasures on display for the public.This is a painting by the artist Yokoyama Kazan. At right is a close up of that dragon. We can see the clouds and lightning: dragons are often depicted with clouds and with lightning, because dragons bring rain.

Rainmaking with Dragons’ Jewels

So how do dragons cause rain? Well, they cause rain through a jewel.

And if you look closely at images of dragons below , like this embroidered one from Abura Tenjin Yama (below, upper left), up there in the upper right-hand corner, dragons are often seen together holding—or reaching for—this jewel.

In this metal work from Hoka Boko float (below right), we can see a jewel on the upper left.

Finally, notice the dragon textile at Ofune Boko, also holding a jewel (below, lower left). These are all dragons in the Gion Festival.

At right is a scroll painting of another dragon holding a jewel. And the aristocratic woman in front of the dragon is also holding a jewel.

What is with this jewel? In Buddhism, there’s something called “the wish-fulfilling jewel.” Sometimes it’s also called “the pearl without price.” These are synonyms for enlightenment.

So Kukai tried and tried, but the dragons didn’t come. Why not? Kukai meditated upon it. And he found that his competitor Jubin had trapped all the dragons. Jubin was so jealous of Kukai that, instead of causing rain, he prevented the dragons from responding to Kukai’s summons.

Good Woman Dragon King Brought Rain

However, one dragon escaped, came to Kukai, and brought rain. It rained throughout the country, and people were saved! The rice grew, people could eat and drink again. And this scroll depicts the dragon that came.

This scroll painting is from the Ishikawa Nanao Art Museum. This is a dragon known as Zennyō Ryūō (善女龍王). “Zen” means “good” or “fortuitous,” and “nyō” means “woman.” And she’s called “Ryūō,” which means “Dragon King.” So “Good Woman, Dragon King.” “Woman Dragon King.” This is kind of strange.

So what does this mean? How can she be a woman and a king at the same time?

The Lotus Sutra & Dragon King’s Daughter

Well, there’s a very famous sutra called the Lotus Sutra in Buddhism. And one of the main features, or the main people featured in the Lotus Sutra is someone called “the Dragon King’s daughter.”

She was a young girl dragon, or young woman dragon. And Manjushri, the bodhisattva of wisdom, praised her for her wisdom, her compassion, her understanding of the sutras, and her enlightenment.

And one of the Buddha’s disciples said, “What? That’s impossible because …” and she was there, and he said, “you can’t get enlightened in a woman’s body.”

Dragons & Enlightenment in a Female Body

And this was a very common thought for many centuries in Asia: that it was impossible to get enlightened in a woman’s body. And that, if a woman wanted to get enlightened, she would pray and pray and pray to be reborn as a male, and then she could get enlightened.

Well, when the Dragon King’s daughter heard this from one of the Buddha’s disciples, she instantly changed her shape, and became a man. And then became known as a Dragon King, and a protector of Buddhism.

So this is my personal theory: that’s why this dragon is called, in Japanese, “Woman Dragon King.” It bears further research, and I look forward to looking into this more.

For many centuries, this was the only female known to have gotten enlightened. She was a really great inspiration to many women practitioners and Buddhist nuns for many centuries, as a role model.

Today it’s believed that she lives in the lake at Shinsen-en (right). Why is this significant for the Gion Festival?

Shinsen-en Lake & Gion Festival’s Origins

Well, Shinsen-en is also where the Gion Festival began. So let’s go to that. Let’s go to the roots of the Gion Festival.

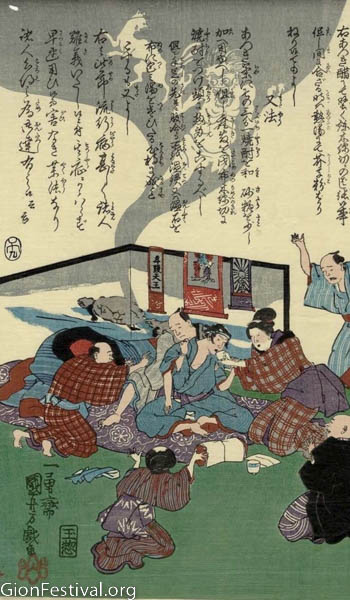

What we know as the Gion Festival started in the year 869, and in those years, there was, on average, an epidemic every third year. At left is an historic wood-block print. The rising grey smoke, with the spirits in it, is believed to be the epidemic. These are people tending to a sick man.

Summer Storms, Epidemics, & Angry Spirits

It was believed in those days that epidemics were caused by angry spirits or vengeful spirits. There was an epidemic every three years. So they believed that some spirits were really angry. Of course, today we know that epidemics are caused by germs.

In those days, well, there’s still something in Kyoto that called the “summer sickness,” and that’s related to the rainy season. It would rain a lot, there would be standing water, and then there would be things like cholera or dysentery that would go around.

Remember, the main deity in the Gion Festival is Susano-no-Mikoto, the god of storms (below image, center).

And it’s said that in the year 869, there was a terrible epidemic, so bad that the the rivers were filled with corpses. So in 869, they had a gathering. The emperor called for a great ritual at Shinsen-en, to appease these angry spirits, to ask them to stop being angry and take away the epidemic.

We can only guess that it worked, because they kept doing the Gion Festival. If there was another epidemic, they called the same kind of ritual. And by the year 1000 it became an annual event, and it became the Gion Matsuri that we know today.

As we know, if we don’t have epidemics, that’s a good thing. Hopefully, that means that everything is fine.

But then there’s the opposite problem: if there’s not a surplus of rain, maybe there’s a deficit of rain, and maybe there’s drought. And so then remember that the soul of rice, Princess Kushi Inada (image above, left), is also one of the main Gion Festival deities.

So with the rainy season, we can have too much water and floods and illness. Or we cannot have enough water, which leads to droughts, not enough rice—because rice grows in water—and famine.

Gion Festival & Climate Change

This is a very interesting thing to look at now in the 2020s, when we’re living in an era with significant climate change. These are all stories about what happened in the ninth century, but it’s relevant for our world today as well.

So human relationships with dragons (left, from Minami Kannon Yama) have been used for at least a millennium to try to find a balance between too much rain and not enough rain.

Dragons, Enlightenment and Kundalini

We’ve addressed dragons and energy, elements, and the Woman Dragon King getting enlightened. Let’s take another look at dragons and enlightenment.

Above left is an image of part of the meeting place, shrine, and display area for Koi Yama: “Koi” means “carp.” And you can see the figure of the koi there in the background, in the center. Then Above right, there’s a close up of this carp at Koi Yama.

You can see the koi is amidst some water, and it’s kind of going up. It’s swimming up a waterfall.

There’s an ancient Chinese tale about a carp that swam up a waterfall: when it got to the top of the waterfall, it became a dragon. This is a wonderful legend, and it’s very well known in Japanese culture. This is one reason that carp or koi are so popular in Japanese culture.

This image at left is a painting of koi by a famous artist, Kimura Hideki, that they put out during the Gion Festival.

And you can see there’s a little bit of writing in the lower right of that painting, which is shown close up in the middle image. The artist wrote, “Carp is dragon in heaven.” This is a nice way to refer in English to this going up the waterfall and then becoming a dragon.

So from a folklore kind of perspective, this relates to prevailing against the odds, which we can all relate to. It’s a very human experience.

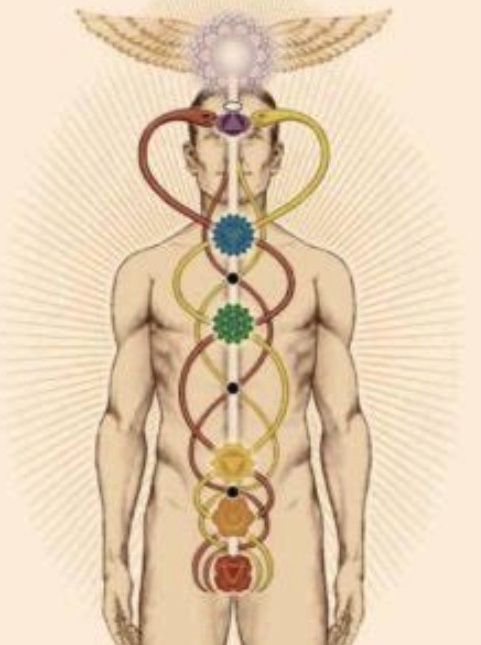

And more esoterically, this also relates to the experience of enlightenment, because it’s said that energy is released from the base of our spine, and travels up our spine, up to our crown chakra. This is a kind of chakra experience: the energy flowers there at the crown of the head. If you’re familiar with yoga, you may have seen images of a lotus at the crown of a person’s head.

And so this kundalini rising, or energy-rising experience, is one of the hallmarks of the enlightenment experience. So that’s a more esoteric meaning of this carp becoming a dragon legend.

Interestingly, at Koi Yama, they have a kind of tagline there, which is called “Dragon’s Gate.” And I thought, “Why “gate?” Where does that come from?” So I looked into it a little bit.

Koi Yama Float & Dragon’s Gate Taoism

Interestingly enough, there’s a Dragons Gate in China, an actual place that’s a “dragon’s gate.” There’s a waterfall falling through a kind of hole in the rock. If you were a carp, you would go up the waterfall and fly through that big opening in the rock—the “Dragon’s Gate”—and become a dragon on the other side, at the top of the waterfall.

In this location, a very important school of Taoist philosophy and practice was founded, called “Dragon’s Gate Taoism.”

That may be where this notion of the “Dragon’s Gate” being a symbol for enlightenment came from. And I wrote about this more in my book.

Fune Boko’s Empress & Dragon King

Let’s talk about another dragon in the Gion Festival. One of the most popular floats at the Gion Festival is this one at left below. It’s called Fune Boko, which means the “Ship Float.”

It’s called the Fune or “Ship” Float for obvious reasons. It’s in the shape of a ship, and it’s one of two floats in the festival with this unique shape, which makes it very popular. It’s very charming.

Why a ship? There’s a story behind this. In the 500s—this is before recorded history in Japan—Japan’s oldest texts say there was a woman, they call her “Empress Jingu.” But in those early days, she was probably more like a tribal leader, like a head of a small clan. At right is the sacred statue of her revered at Fune Boko. The curtains serve to demarcate a distinction between our worldly space and her sacred space.

So, Empress Jingu did a divination. She believed the divination told her to go to the Silla Kingdom, which is present-day South Korea. She got in a boat to go across the great sea to this kingdom, to the Korean Peninsula.

This was a very hazardous journey in those days, and the ship that she had was probably not as grand as the Fune Boko. It was probably more like a small boat. She needed help.

Dragons & Empress Jingu’s Success

The ancient text tell us that she received support from the Dragon God, or Ryūjin in Japanese. The image below left shows a sacred statue of him at Fune Boko, where he’s revered along with Empress Jingu. Note that he’s holding a tray with two jewels.

In the image below right, you can see the Dragon God, behind the guy standing with the towel on his head. You can see his red hair there. The Dragon God is right at the prow of the Fune Boko, guiding Empress Jingu. And Jingu is further back in the ship or float, meaning that the Dragon God is guiding her where to go.

Why is he doing this? Well, because dragons rule water, and because he’s got these jewels.

Remember these jewels? These jewels are considered life-bringing, they bring rain. They’re considered synonymous with relics of the Buddha. They’re considered synonymous with enlightenment in Buddhist thought.

And in the story of Empress Jingu—which predates Buddhism in Japan—the jewels were said to control the tides.

The assistance from the Dragon God allowed Empress Jingu to travel across the seas safely, and allowed her to land safely in the Silla Kingdom and on her return.

And reportedly her trip was a great success: she came back with tribute.

Fune Boko has a lot of dragons associated with it. Is this celebrating the support of the Dragon God, key to Empress Jingu’s success?

Above right we see a blue dragon textile on the side of the Fune Boko float. Below left we see a beautiful mother-of-pearl dragon—again, amidst water—that’s the rudder of the Fune Boko “ship,” at its rear. At lower left is a textile on the side of the Fune Boko float. Below right is a beautiful textile on the front of the ship. A lot about dragons.

When Empress Jingu came back from the Silla Kingdom, she came back in the second boat-shaped float in the Gion Festival, which is in the Ato Matsuri, the second half of the Gion Festival. This second boat-shaped float, shown at right, is called Ōfune Boko. “Ō” here means “big” or “great,” so it’s, the Great Ship Float. It’s bigger than the Fune Boko.

Why is it bigger? Because Empress Jingu came back with lots of tribute, with lots of treasure. And a dragon at the front of the boat guiding her back, a beautiful gilded dragon sculpture Here’s a close up of the dragon at the prow of the Ofune Boko.

As I’ve said said, there are a lot of different dragons shown throughout the Gion Festival. There are wooden sculptures like this one. There are statues like the Ryūō or Ryūjin, the Dragon God or Dragon King.

Dragons in Gion Festival Textiles

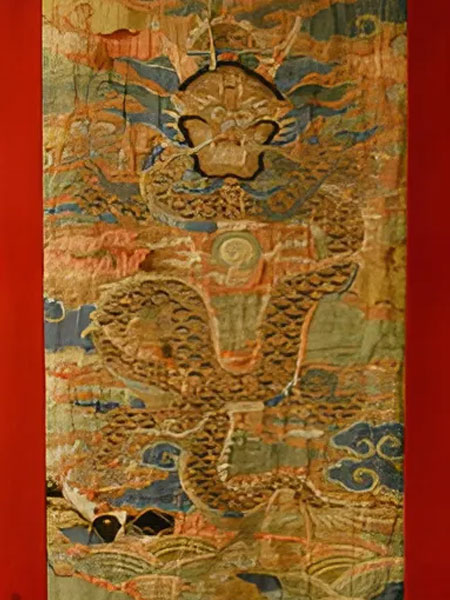

There are many more really beautiful textiles depicting dragons in the Gion Matsuri. We have seen a few here.

Below right is a modern reinterpretation of a much older original at left , both at Fune Boko.

The new ones can be easier to enjoy because the colors have not faded. But in general the older ones are more skillfully woven, and are more valuable.

Until relatively recently the original was still being hung on the Fune Boko during the July 17 procession, when the floats go through the city streets. Most communities are decorating their floats less and less with their antique textiles, for conservation purposes. You can see it has experienced some wear and tear, and it’s several centuries old.

The mood of the era has turned much more towards conservation. This is thanks to the work by Nobuko Kajitani—who used to be the head of textile conservation at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York—and by Yoshida Kojiro, who is very involved in the Gion Festival.

They wrote a book together on the non-Japanese textile collection in the Gion Matsuri. It’s a very unique and amazing collection, spanning centuries and with pieces from many countries around the world. Consequently the Gion Matsuri textile collection is very well known in the international textile community.

Gion Festival’s Chinese Imperial Robes

Here’s another valuable antique dragon-themed textile from Fune Boko. It used to decorate the float, and is now in conservation. We can see that there are some seams on it. What’s up with the seams?

Some of these were imperial court robes that got repurposed. They were taken apart and resewn to form what are called jūtan, or textiles. They then decorated the exteriors of these Gion Festival floats for centuries.

There are a good number of these ancient imperial textiles.

Below we see one decorating Arare Tenjin Yama. You can see on the side there’s a dragon textile. And looking more close up, we can see the main dragon has, indeed, five claws. So that’s pertaining to the Chinese emperor.

Why are there so many of these textiles in the Gion Matsuri?

Interestingly, when a dynasty changed in China, the new dynasty didn’t really want these old imperial robes that belonged to the previous dynasty. Because it spoke of their power, and they wanted to replace it with their own power. So they wanted to sell off all of these goods.

This was a time when Japan was closed. It was the sakkoku jidai, it was closed to external trading for the most part, except for the Dutch trading on Dejima Island in southern Japan.

Additionally, the indigenous Ainu in the North were excellent traders. Because of the closeness with the continent and the Sakhalin Islands, the Ainu could get goods in from China.

These textiles could get traded all the way down to the Gion Matsuri, which speaks to the mercantile skill of the Ainu.

It also speaks to the power of the Gion Festival community at that time. They could procure these rare and kind of black-market goods that used to belong to the Imperial family in China.

This blue textile with dragons is at Hashi Benkei Yama. Again, we can see some of the seams, and how it may have been taken apart and put together. You can see on the lower half, on the left and right sides, there’s a whiteish part that would’ve been where the sleeves were.

In this image these parts are marked with the pink lines. Perhaps the Hashi Benkei Yama community filled in the robe shape with some other textiles—probably custom-made by Kyoto weavers and embroiderers—to fill in those spaces. This would have made the robe a rectangular shape, size and appearance suitable to impressively decorate Hashi Benkei Yama.

Historic Upcycling

At right is another ancient Chinese textile: we can see the dragon, the jewel, and the five claws, which indicates the Chinese emperor. This is at Hachiman Yama.

Some of these textiles are centuries old, and very valuable. Below right is Kuronushi Yama, known for its sakura blossoms. That horizontal band across the top is one kind of recycled imperial robe, and original.

The upper right image is a close up of that horizontal band, that dragon with the jewel. So some floats still choose to decorate with the originals. Other floats conserve the originals and decorate with replicas. Some float communities choose to commission new textiles that are not replicas of old ones.

In the lower right image above, we see a closeup of the central textile on the front of Kuronushi Yama. It’s from the mid 16th century, and is among the oldest textiles still being exhibited in the Gion Matsuri.

The year I took that image, 2014, was a very special Gion Matsuri. To celebrate, a Kuronushi Yama community member told me, they took it out of conservation at the Kyoto National Museum to decorate the float. This is upsetting to conservationists, but at the same time, as noted earlier, the festival has a lot to do with impermanence.

We can see the seams in the textile, one of the signs that it’s an upcycled Chinese court robe. So for centuries, Gion Matsuri communities have done amazing things with upcycling.

Above we can see some more original textiles being displayed on Ennogyoja Yama during the July 14 Ato Matsuri procession.

Again, the lowest band—with the blue dragon—would’ve been upcycled. You can see the seams; there are strips of textile sewn together. Near the dragons, we can see wish-fulfilling jewels suspended in space.

Sometimes during the processions, or when the floats are out on the streets, the textiles may look a little bland or a little worn. The colors have faded, and they can get a little bit threadbare after centuries of use! But if we look closely, we can see just how well-made they are. And the detail is astonishing.

Conclusion: Dragons in the Gion Festival

Truly, so much of the Gion Festival is about looking closely, to better understand the stories behind every facet of this enormous and ancient purification ritual and cultural treasure. Lots of treasures and secrets are waiting to be revealed, simply through us looking closely and paying attention.

And notice how many of these dragons are blue. So, they refer back to the blue dragon of the East, they refer back to the fact that this Gion Matsuri is taking place in the summer rainy season.

Propitiating dragons also serves as a kind of quest for harmony with nature. Kyotoites have long sought to avoid an excess of water that can bring deadly illnesses, while welcoming enough to ensure the life-giving rice that Japanese people have depended upon for so many millennia. This is one of the universal facets of the Gion Matsuri: wherever we may live, climate change has helped us greater appreciate our need for just the right amount of rain to fall each year.

Co-Creating a Sustainable Gion Matsuri

Thanks for reading. If you’ve enjoyed this blog, please help spread the word. This helps me achieve one of my goals: co-creating a sustainable Gion Matsuri. It’s so extraordinary that it’s lasted for almost 1200 years. I’d really like it to last another 1000 years, so future generations can also enjoy it.

I also endeavor to support the wonderful Gion Festival community, and your support helps me to do that.

You’re invited to like, follow and subscribe to my social media channels—clickable icons are at the top and bottom right of every webpage—and to sign up for my emailing list, very lightly and respectfully used. And if you see me on the streets of Kyoto during the Gion Matsuri, I’d be happy if you stop me to say hello.